07 Feb From The Bardo to the Light

For most of the time that I’ve been creating art, and teaching movement, I’ve done it in secret. Secrecy felt safer. Secrecy felt natural. Secrecy was my shield that protected me from the truth: my art and my creations mean everything to me. If I stayed in the shadows, I could pretend that this was all some lark, and if it all just went away, I wouldn’t care.

But, that isn’t true. The photographs you see on this site. The years of time and care and craft that it took to create them and the ideas behind each one, they really matter to me. The teachings I share and craft and espouse, they are a part of my soul. The stories I weave, are spun from years of study, from hours of care and from the vulnerability of my heart. When you hear me speak, you are listening to my soul, colored by the language of the goddess whispering in my ear, and it does matter to me. It matters a whole lot.

Elizabeth is someone i have known for many years, and in a totally different context. She ran a school my son attended, and then her daughter and my daughter became very close friends. Somehow, I pulled her in to my classes, and she began to use her gifts to talk about my gifts and it was a mirror I didn’t even know that I needed.

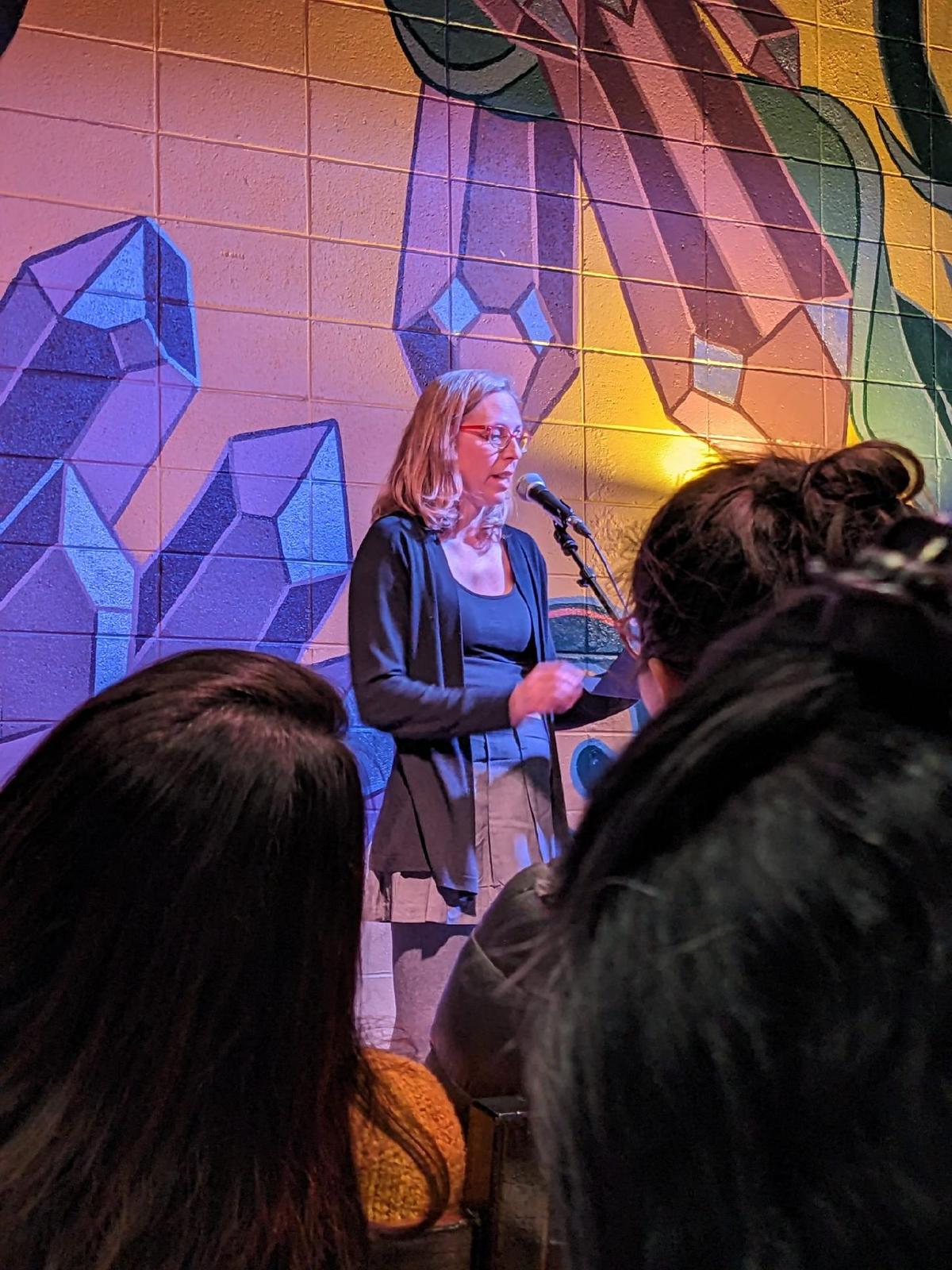

It was very edgy to hear her share about one of my most personal offerings, Death Portal, and share she did. In front of 60 people, at a Story Share, in Boulder, Colorado. The result rocked me, and pulled me firmly out of my shell. And made my heart race, and my eyes widen and my palms sweat, but it also made me, once and for all, take ownership of my OWN work. And declare, it really does all matter to me.

Dance Class

I have never been much of a dancer. I can hold my own in a late night kitchen dance party, but after the failed experiment that was me enrolling in African Dance class during college, I had to make my peace with all my straight lines and angles. I just didn’t have all the right curves in all the right places.

But then I met Liz. We connected because of where our children were attending school, and then our girls ended up staying an extra year together at their nursery school during the first COVID year, and they fell in love. We had to keep them connected, so we just kept doing playdates, to keep their sweet friendship alive. And eventually Liz started inviting me to what she called “dance class”. I was curious, because I knew that she taught the class, and she had always felt to me a little otherworldly, a little more in touch with things that most people can’t see. A beauty in her early 40’s, Liz is also the creative genius behind her husband’s thriving cosmetic and medical aesthetics business. I knew she did photography as well, as part of her personal art projects—and her photos of women ranged from sweet and sensual, to raw and messy, erotic and exposed. Naked women covered in mud, bathing in a creek. Women in rakish makeup, finger on lips, daring you. Women in fields with their arms outstretched, wearing white slips, running free. All of the photos playful, all of them granting permission.

Eventually Liz clarified for me that she and the other women didn’t really dance at dance class. In fact, she said, I would likely be a worse dancer, a forever weird dancer for having gone to dance class. It was more that they allowed things to move through them, that they were in community together, and I just really needed to come and see. And so at the end of last summer, maybe because I needed something new to happen, I went. I felt shy, a little frozen with all these women so free, so beautifully themselves. But I just kept going. “Has this been good for you?” I asked one woman—“It’s been the best.”, she answered.

The other dancers were mostly younger than Liz and myself, some of them mothers to young children like me, but others were in their early 20’s and I felt something like jealousy that they were already developing this kind of relationship with their bodies, at such an early age. When these women moved, I felt things because they expressed things. Powerful emotions surfaced and receded, dreams were held in outstretched arms, pain flickered across faces, ecstasy at being alive following close behind. Each one of them held their hearts out, vulnerable and honest—and if you have never been in a room with 14 completely open hearted women, what I can say is that revolutions are born from less. It took me months of moving with these women, but I started to feel something cracking open inside of me. I started to understand why we had to strip down to our underwear and move to a thousand different songs, in countless ways, just to make peace with our bodies and learn to celebrate them. How the wisdom of the ancients, and the gods and goddesses Liz was always calling in to come join us, could help us find reprieve and solace for our minds. Why we had to let our hearts pound with the din and the madness of life, and then come back afterwards to the warm nest of love that was each other.

Dance class, in the purest sense, is a circle of women dancing at Stonehenge, playing with the in-between spaces between the world we inhabit, and the one that is just out of reach. A modern day group of poets, healers, muses, and dreamers, we willingly step through the veil, with Liz as our guide. In ancient times, this type of other-world walking was a more common practice. At the very least, there were times in history where it wouldn’t have raised as many eyebrows to be on speaking terms with archangels and goddesses, or to have visions and dreams that foretold the future, or shared with you a few secrets of living, from the realms of the dead. In the cradle of the deep, I have danced my way through my relationship to the seven deadly sins, the passage of time and the seasons, my deepest desires and secret pains, what I wish to shed and subsequently what I choose to call in to my life. I have moved through every stage of my development in my mother’s womb, from before the egg and sperm ever shook hands, to the time when I was finally, desperately released into the world, brand new. I have been reborn more than once at dance class. Let us just say that Liz and the participants of dance class would not have faired well during the Salem Witch Trials.

Never was there a more poignant example of what dance class would do to me, and for me, than a class called Death Portal. This was exactly what it sounds like. There were 8 of us, plus Liz, and we were told to show up to class ready to leave something at the altar of death, knowing full well that we wouldn’t get it back. We knew we were going to have a funeral and that we would be reborn, but otherwise, we didn’t get much information. Liz spent weeks carrying our souls around, preparing to do this work with us. By the time I went to death portal I knew that Liz had also been researching ancient death rituals for months beforehand. We dressed simply, with no jewelry, because in ancient times all people had to come as equals to the threshold of death, there was no place for class in the underworld, no place for some souls to have shiny bobbles and others not.

Typically, we would have gone straight down to Liz’s dance studio for class, but on this day, we began in the “above” human world, to get clear on our journey before we descended into the depths of the underworld. Because we weren’t the ancient Greeks and couldn’t begin by bathing seven times in the sea, we washed our hands seven times—all of us serious, a little somber even, some of us nervous to go through our first death ritual. Liz believes, as the ancients did, that a person must die every year in order to fully live. As one of our group said, “Perhaps this is why we have so many suicides. There is never a chance to stop living, to leave this life, and then to willingly decide to come back”—with the full knowledge, of course, that you get to choose what you wish to leave behind in the underworld. I suppose even I showed up to death portal that day because a part of me wanted to die. I don’t think you can be a human on this earth, and not feel at times like it’s all just a bit too much. And so, as I walked up to Liz’s door that day, my thought as I entered was, I’m ready to die.

Liz gave us tethers to tie somewhere on our body, to remind us that we were not in fact dying in class that day. The tethers were to remind us, were we to go in so deeply, that we still had a life, and things to live for. She then asked twice for our consent before we descended into the dance studio, ashes smudged on our foreheads, holding a candle and a stone in our hands. We were to leave the stone at the altar of death, as the thing we were willing to leave, something that no longer served us, a thing we would never get back.

On any day, walking down to the dance studio is much like walking onto a stage at a live theater performance. When I arrive, I suddenly discover that I am one of the players, except for the fact that there are no scripts and the experience feels too real to be a part of a play. The only real cues we are given are in the form of the environment, which is always set up differently, and Liz’s voice, overlaid on top of very intentionally chosen songs. On the day of death portal, the space had been transformed, and was, every inch, the underworld. We had each been assigned a grave, which was a black sheet covering a sheepskin lying on the floor. Our graves had a mirror and a vase of dead flowers, and above our grave we found a picture of ourselves–many of us smiling in much younger faces. My picture was of Elizabeth at 5 years old, eyes bright, with a shy sort of questioning smile on my face.

We wandered around the underworld for a while, everything normally available to us shrouded in black: no soft pillows or cozy blankets, no Japanese floor mattresses, no dress up clothes or lingerie, no snacks, chocolates or bubbly water. Instead, the temperature of the room had been left intentionally cold, the ground bare except for our graves, making the hair on my arms stand up. With Liz coaxing us along, we each eventually placed our stones on the altar and made our way to our graves.

Around our necks hung 7 necklaces, each representing an illusion of life that we had to shed in the underworld, in order to fully die. As the journey was well under way now, we sat at our graves and moved through 7 songs, each one coaxing us to give up an illusion, and to drop, one by one, our necklaces into a glass bowl by our grave. Fear, pain, my physical body, my mind, my creations (including my children), my name, and my form. I particularly struggled to give up my mind and my creations, but the hardest of all was my name. Later, in our time of reflection, one of our group shared, “I felt that if I gave up my name, then how would God know who I am?”, and another one shared, “I imagined my tombstone knocked over, my name rubbed off, and so much time had passed that the idea of me didn’t even exist anymore.” And for myself, I felt the identity of my name like the last critical tether to my life. I was able, for the first time, to imagine how it felt for my dad, right before he died. I could feel how tightly we hold onto these illusions of self. I know the night he died, a nurse at the hospital had a long conversation with him and she said, “You have done so much, it’s time to rest now.” And I think that was what allowed him to finally let go. It was the idea of laying it all down, of having nowhere to run to, even risking that we will be forgotten and the very idea of us may drift off on the wind and it will be as if we never existed. When I dropped the illusion of my name, I felt quiet inside, like there was nothing left to differentiate me from the rest of the vast and unfathomable void. And then, once we released the illusion of form, we were dead.

As the oldest in the group, my funeral was first. As everyone walked up to my grave, all of them in black, and I stood there watching them, I felt completely exposed. I had to drop to my knees, it was so humbling, so powerful. As my funeral songs started to play, I felt the struggle in myself. I actually didn’t want to die, I was attached to living, I was attached to being me. But as the music played and I moved my body, a sort of softness crept over me, and I felt that death has a quiet power too. I felt how much I needed to die to myself, and how badly I needed to be reborn, as a new version of Elizabeth. One of my funeral songs was a plea—to meet me in the mystery, and I felt it as a plea to the universe; “See me through to the other side.” When my funeral ended, Liz, covered me with a black sheet, head to toe, saying, “Rest in peace, dear Elizabeth.” and everyone moved on to the next funeral. They all just walked away and left me there alone. I wanted to experience their funerals too, but as one of our group reflected, “That’s what death is like, isn’t it? You do miss out, you don’t get to exist anymore”.

At the conclusion of the funerals, we paused to reflect on what we wanted to take with us into our newly chosen lives, and then we were awakened back to life by being anointed with spikenard oil, the same oil used on Jesus after the crucifixion. I felt stiff, as if I really had been laying in a grave. But I felt relief too. I wanted to live. And then the party started, and we danced our dances of rebirth while still in the underworld—we were given laurel wreaths as crowns, chocolate to eat and sweet liquor to drink. And we celebrated with each other, by dancing and mirroring each new soul who was choosing to be reborn into this life. I moved in 8 new ways, as I danced alongside each person whose song was playing. As Liz says, maybe we always think the same things because we always move the same way—and this is why we need community. We need to be prodded into moving in new ways, so we don’t miss out on the literal fullness of ourselves.

What I left at the altar of death was an old habit of mine to minimize myself and my experiences in life. No longer willing to play small or make myself wrong, I left that behind in the underworld and now I have no choice but to live into the fullness of Elizabeth. At the end of class, we ate a metaphoric meal, crafted by Liz’s creative assistant and culinary genius, Brenna, so we could taste the richness and gravity of life. Over the meal, we reflected on the experience of death portal. An ancient ritual brought into our modern time, but just as critical, and just as deadly. And for the first time, I have a new, additional understanding of that word, deadly. I think now, it also represents the freedom we experience when we make the choice to die, so that we can actually live. Used by a teenager in the year 2065 when it finally gets added to the urban dictionary, it will sound like, “That’s so deadly, she could have quit but instead she just completely started over.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.